As many artists who have studied with me over the years know, I have long been fascinated by Leonardo da Vinci’s seamless connection between science and art. My own interest is no doubt heightened by a shared love of geometric forms—especially the circle and the sphere—but even more by Leonardo’s deeply rooted belief that art and science are inseparable. That conviction lies at the very heart of botanical art, where observation, structure, light, and form must work together with both sensitivity and precision.

So, I was especially intrigued when a fellow Canadian—now living in the Philippines and new to botanical art—told me about a remarkable book: The Shadow Drawing: How Science Taught Leonardo How to Paint by art historian Francesca Fiorani.

For centuries, it seems a myth has existed that there were “two Leonardos”: first the artist, then later in life the scientist. Fiorani has questioned this tidy division. Drawing from Leonardo’s notebooks and contemporary sources, she demonstrates that he became fluent in scientific thinking as a young apprentice in a Florentine studio. His interest in optics—the science of light, shadow and vision—was not an afterthought. It was foundational. It permeated his creative process.

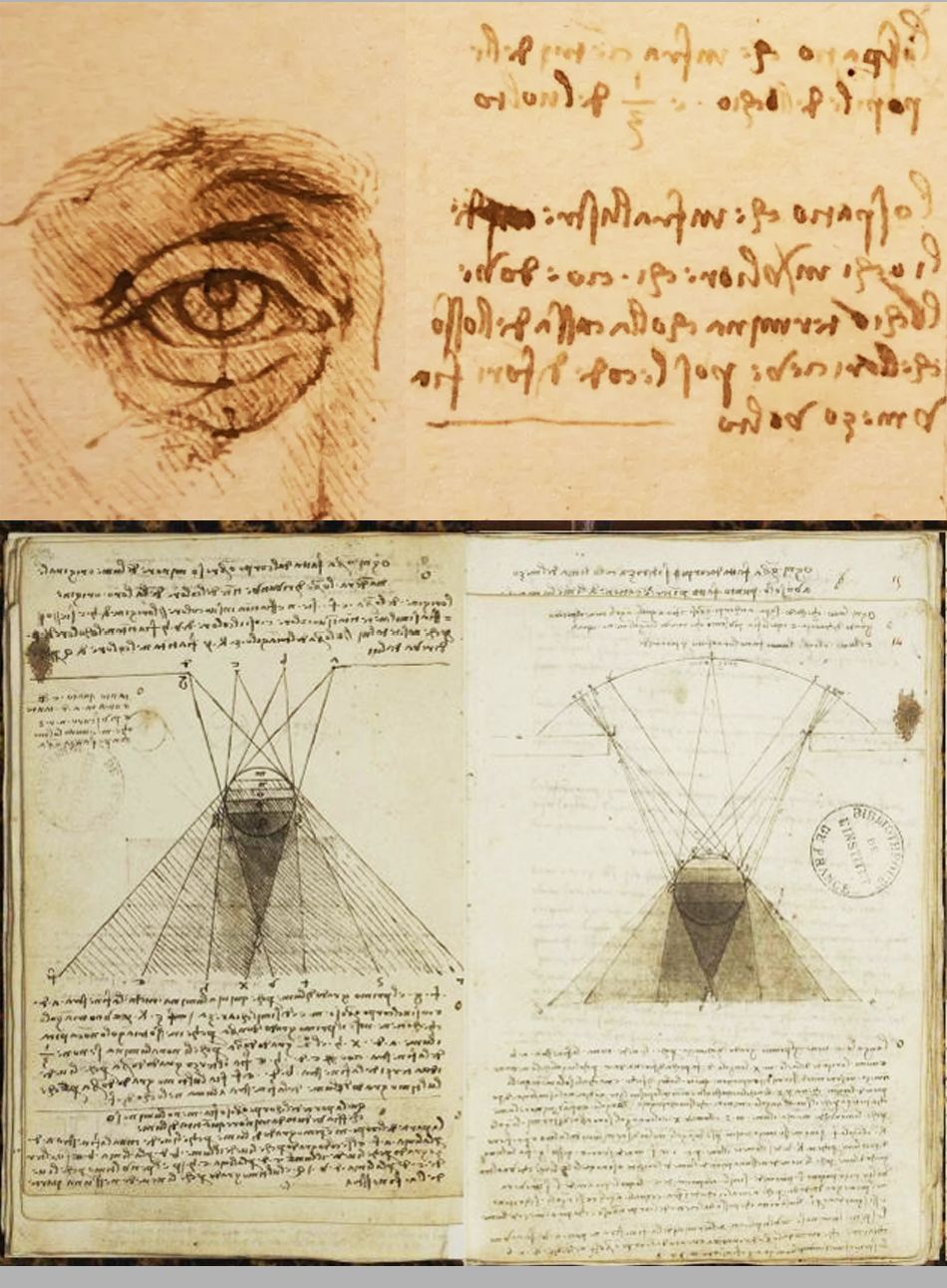

Leonardo studied how rays of light strike the human face or an object at different angles, how illumination shifts across curved surfaces, and how shadows vary in softness and depth. In his notebooks, he diagrammed beams of light contacting a form, carefully observing how differential illumination secures dimensionality. This was not abstract curiosity, nor was it a shallow and merely intuitive response to light and shadow. Instead, he applied a calculated, mathematical understanding of optics coupled with intense personal observations directly to his painting. Leonardo believed the eye did not lie.

The results were revolutionary.

Through his study of light and shadow, Leonardo achieved an unprecedented realism. He could model the subtle turning of a cheek, the almost imperceptible movement of human expressions. His famous sfumato—those seamless, smoky transitions between light and dark—reflects an optical truth: we do not see hard outlines in nature, but gradual tonal shifts and contrasting edges shaped by light and by optics. By mastering the science of optics, Leonardo sought nothing less than to capture the interior life of his subjects—the tender, fleeting motions of the human soul, the delicate folds and curls of an aging leaf.

For those of us engaged in botanical art, this integration feels especially meaningful. To render a sphere-like fruit or the curve of a petal convincingly, we must understand how light wraps around form. Leonardo’s insight reminds us that accuracy in intense observation is not cold calculation; it is a pathway to expressive truth.

In The Shadow Drawing, Fiorani offers not just a biography but a powerful reconsideration of Renaissance thinking—an era when art and science were partners, not rivals. Leonardo did not paint despite his science. He painted because of it.

And perhaps that is the enduring lesson: to truly see is both an artistic and a scientific act.

* Shadow Drawings from Leonardo da Vinci’s notebook – Bibliotheque de l’Institute de France in Paris.